Tommy Robinson, the right-wing cult hero who's spearheading a massive demonstration in London on 13 September, Tweeted Wednesday:

Upon seeing Hitchens' name mentioned and quoted, we couldn't help but notice that we have on record in our archives his last interview. The interview was first published in the Winter 2006 edition of The Internationalist, which has since folded.

The article, written by journalist and lawyer Jared Irmas, elicits many of the original misgivings anti-immigration pundits today often espouse as the root causes for the cultural degradation of western societies in recent years.

Here we are pleased to re-publish, with kind permission from the author, the interview for the first time since it went to print in The Internationalist:

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS AT WAR

Christopher Hitchens turned from anti—war hero to pro—war crusader. He was a champion of the Left and, later, its biggest defector. He has no regrets.

On a crisp New York City night stuck between winter and spring, couples stroll across Washington Square Park surrounded by the citadel of New York University. On the tenth floor of the student union building, looking out on the gleaming midtown skyline, a young Lebanese man dressed in black is maneuvering his way through a crowd to yell at Christopher Hitchens.

“How can you promote a double standard by defending the Danish right to publish hateful cartoons, while you bash Hamas for publishing material on their website?” the Lebanese asks sternly, getting close to Hitchens’ face.

Hitchens stands there delighted, his only concern an unsmoked cigarette dangling from his fingers. He wears a pin proudly on his lapel jacket. It reads: “ALL THE RIGHT ENEMIES.”

Hitchens has just stepped down from the stage where he participated in a public panel on the Arab-Israeli conflict and managed to piss off both Arabs and Israelis. Whether invoking an old joke (“Never sleep with an Israeli because they always promise to withdraw and never do”), observing that Christians support Jews like “rope supports the hanging man,” or labeling both sides of the conflict as having been taken over by “toxic fascism,” Hitchens topped off his performance by bringing up the most controversial position of his career.

“We did not make an attack on Iraq,” he said before the crowd of a hundred New York City students and academics. “We made an attack on Saddam Hussein, which was completely justified and long overdue.” As if he were expecting them, Hitchens hid his smile as the “boos” and “tisks” came flying from the crowd.

In 1998, a friend arranged for Hitchens to have an Iraqi exile over to his apartment. The man’s name was Ahmad Chalabi, the now-notorious intelligence-peddler who helped the Bush administration make the case for an American invasion of Iraq, in part, by feeding The New York Times stories about stockpiles of WMDs.

“I know how to take down Saddam’s regime,” Chalabi had said over dinner, according to Hitchens. Hitchens was immediately won over to the cause.

“He’s a political genius,” Hitchens says of Chalabi. “He was able to work out how to change the mind in Washington, and I helped him where I could do that. I’m very proud of it. I’m supposed to be ashamed apparently of this conspiracy, but I’m not in the least.” Hitchens looks at his watch. It’s nearly 11:00 p.m. “Maybe we should grab a piece of meat,” he says.

Double standards

At the brightly lit French bistro down the street, the only kitchen open at this late hour, we sit down at the table, and Hitchens orders more scotch and steak tartar. “I turn on my email every morning, hoping I won’t see one of my friends there has been killed,” Hitchens says of his Iraqi friends and commitment. “They get up every morning and get in their car and hope somebody hasn’t bought one of their bodyguards. What credit do they get in The Washington Post?”

“None,” he says dramatically, drawing out the word. “None.”

Back at the elevators, Hitchens stands toe to toe with the young Lebanese. “When I’m for Danish free speech, what’s the fucking double standard?” he retorts in his signature orotund British accent.

“It’s a double standard when you’re for Danish free speech and against Hamas’s free speech!” The elevator doors open. Hitchens steps in, but not before leaving the young Lebanese with his last retort. “Oh yes,” he says with mock sympathy. “We all remember those Danish suicide bombers.”

Ten minutes later, the young Lebanese will be in Hitchens’ face again, cornering him outside the building, as Hitchens stands there smoking his long-dangled cigarette and enjoying every heated word. Arguments are his bread and butter, and these days, he’s in no short supply of them.

The Civil War Within Islam

Christopher Hitchens is perhaps the most controversial and prolific pundit influencing public discourse today. As a man of letters, he punches out a weekly column for Slate, a monthly book review for The Atlantic, a bimonthly feature in Vanity Fair, and publishes a book a year. His papers, when compiled definitively, will likely span half a dozen volumes. He has reported on conflict from some of the world’s most dangerous hotspots, including every country in the “axis of evil.” On television, he brings a British prep-school eloquence and dark wit to a forum dominated by red-faced blowhards posturing for their target demographic.

Hitchens began his career in his native England. An ardent young socialist, he cemented his reputation in the pages of British publications war Hitchens against the hawkish Charlton Heston during live coverage of the first Gulf War. Agitated by Heston’s talking points, Hitchens insisted that the actor list the countries that border Iraq. Unable to name any, Heston scolded his opponent for “taking up valuable network time giving a high school geography lesson.”

“Oh, keep your hairpiece on,” Hitchens replied.

Soon after Hussein’s army had ignited Kuwait’s oil wells and retreated back to Baghdad, Hitchens ventured out to the Kurdish area of Northern Iraq to write a piece for National Geographic. There, he saw the ruins of Halabja, where Hussein’s planes had dropped bombs full of poisonous mustard and sarin gasses, killing an estimated 7,000 people. “That was horrible,” Hitchens says quickly, “and very educational.”

After seeing firsthand the kind of destruction and devastation a single dictator can produce, Hitchens witnessed history repeat itself in Sarajevo, under siege from Slobodan Milosevic’s brutal Serbian militia. “It was a continuous rain of shells and bullets,” Hitchens says. “There was nowhere in the city where it was safe. I never expected to see anything like that in my life.”

But the Blumenthal affair was only a taste of what was to come. After 9/11, Hitchens railed against the Left, berating them for their inability to face the threat of what he termed “Islamo-fascism.” Soon after, he resigned from The Nation and went on to declare himself a fervid supporter of the military intervention in Iraq.

Hitchens culminated his political transformation with a reluctant endorsement of George W. Bush during the 2004 presidential election. The Left had lost a champion and the Right had procured an astute defender of the war. Pro-war hawks, dissatisfied with Bush’s simplistic defense of the Iraq war, learned to depend on Hitchens for an arsenal of arguments when WMDs would no longer do.

“I didn’t tell you the rule of the house,” he says, opening a pack of Rothman’s cigarettes and striking a match. “Don’t ask me to pour you another drink. I can’t be bothered. If you don’t have a drink, it’s your own fucking fault.”

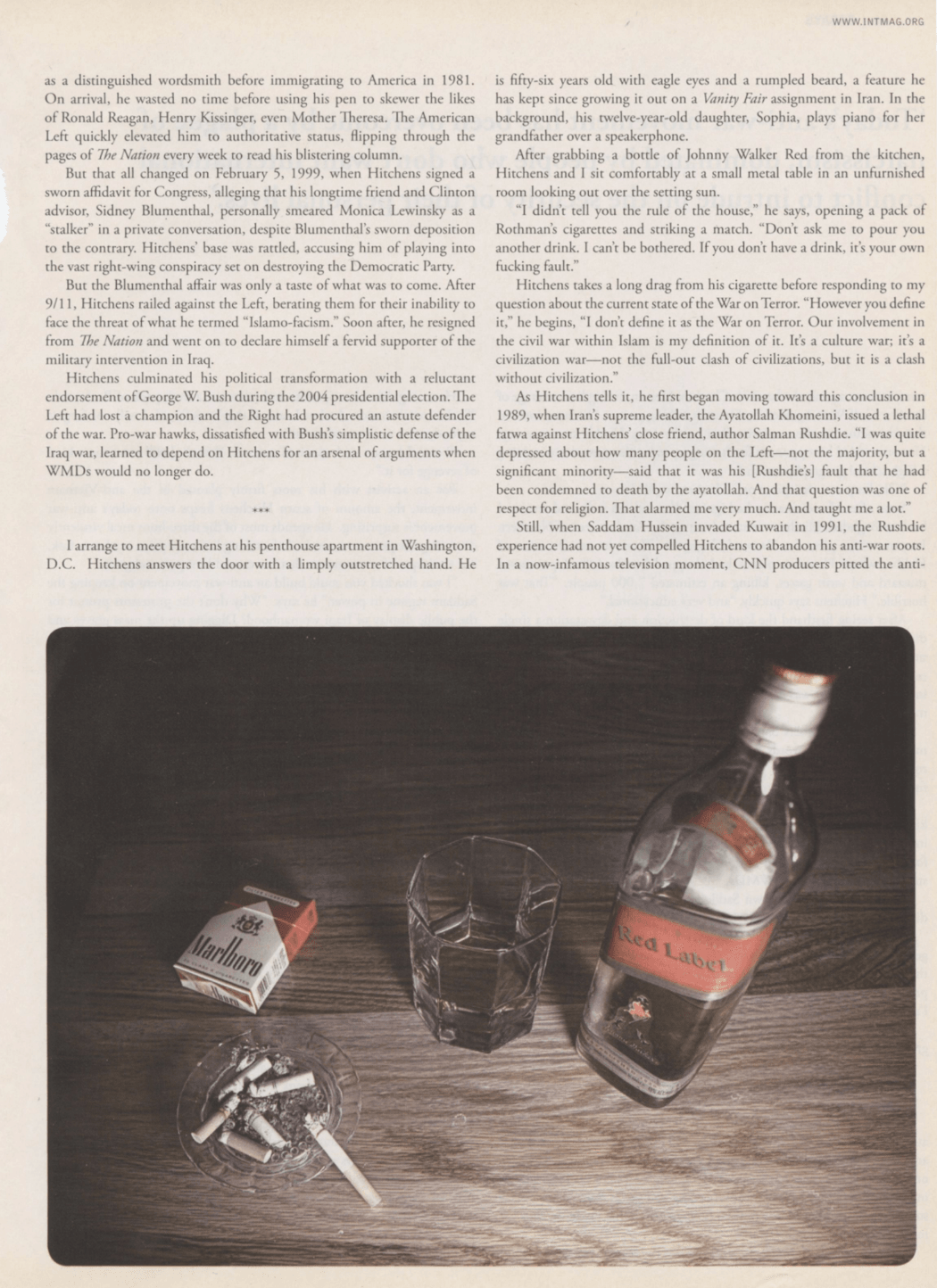

I arrange to meet Hitchens at his penthouse apartment in Washington, D.C. Hitchens answers the door with a limply outstretched hand. He is fifty-six years old with eagle eyes and a rumpled beard, a feature he has kept since growing it out on a Vanity Fair assignment in Iran. In the background, his twelve-year-old daughter, Sophia, plays piano for her grandfather over a speakerphone.

After grabbing a bottle of Johnny Walker Red from the kitchen, Hitchens and I sit comfortably at a small metal table in an unfurnished room looking out over the setting sun.

“I didn’t tell you the rule of the house,” he says, opening a pack of Rothman’s cigarettes and striking a match. “Don’t ask me to pour you another drink. I can’t be bothered. If you don’t have a drink, it’s your own fucking fault.”

Hitchens takes a long drag from his cigarette before responding to my question about the current state of the War on Terror. “However you define it,” he begins, “I don’t define it as the War on Terror. Our involvement in the civil war within Islam is my definition of it. It’s a culture war; it’s a civilization war—not the full-out clash of civilizations, but it is a clash without civilization.

As Hitchens tells it, he first began moving toward this conclusion in 1989, when Iran’s supreme leader, the Ayatollah Khomeini, issued a lethal fatwa against Hitchens’ close friend, author Salman Rushdie. “I was quite depressed about how many people on the Left—not the majority, but a significant minority—said that it was his [Rushdie’s] fault that he had been condemned to death by the ayatollah. And that question was one of respect for religion. That alarmed me very much. And taught me a lot.”

Still, when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1991, the Rushdie experience had not yet compelled Hitchens to abandon his anti-war roots. In a now-infamous television moment, CNN producers pitted the anti- cause when I was poor and when I was less poor. It never had to do with money.”

Back at his apartment, over a final drink, Hitchens sits back with a freshly-lit cigarette and reflects, with tired voice, on the passions that keep him challenging the status quo, and in effect, rendering himself unpredictable.

“One of the pleasures of life is to go back to a country that you knew when it was a dictatorship and a slum, when your friends were in prison or in exile, and see the prison gates broke and them back, publishing newspapers and running for parliament. It is the greatest pleasure I’ve ever had,” he says, exhaling a cloud of smoke. “And I live to do it in a few other places before I check out.”